| Summary | 6th WHITRAP World Heritage Dialogue |

| PublishDate:2022-12-27 Hits:2951 |

|

WHITRAP Shanghai World Heritage Dialogue Rethinking the Contribution of “Connecting Culture and Nature” to the World Heritage Convention

For the video of the activity, please visit: http://heritap.whitr-ap.org/index.php?classid=12497&id=47&t=show

01 Background

The 6th Dialogue was devised and chaired by Marie-Noël TOURNOUX, Project Director WHITRAP Shanghai and co-organized and moderated by Prof HAN Feng, CAUP Tongji University, China; VicePresident of ICOMOS-IFLA International Scientific Committee of Cultural Landscapes(ISCCLs).

Six experts from the Asia and Pacific Region and Peru discussed Rethinking the Contribution of “Connecting Culture and Nature” to the World Heritage Convention.

Image: Group Photo

02 Opening

After welcoming the participants and audience, the Chair introduced the aims, participants, and agenda of the 6th Dialogue.

She invited the participants and audience to consider if bridging the divides and differences between nature and culture and addressing the nature-culture linkage, improved, or not the understanding of what has value and did it allow for the improvement of conservation and management of heritage. She highlighted that a key feature of the World Heritage Convention was to link the conservation of cultural and natural heritage in one single statutory document. However, the operational approach to the implementation of the Convention reflected a conceptual and institutional divide because, in most areas of the world, there are distinct bodies in charge of cultural heritage conservation and natural heritage conservation, each bearing different professional skills and know-how referring to different legal frameworks. Therefore, the Contribution of "Connecting Culture and Nature" to the World Heritage Convention should be reconsidered.

03 Introduction

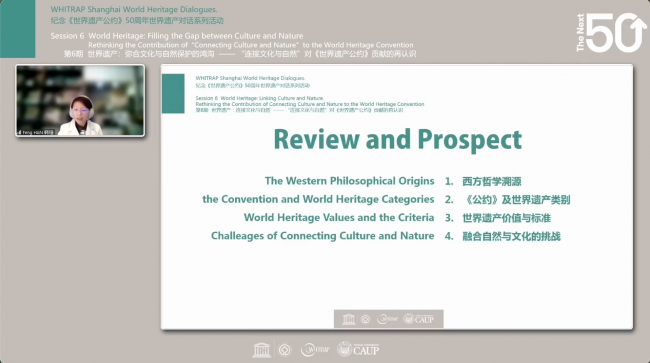

Image: Prof. HAN Feng

In her introduction to the session’s theme Filling the Gap between Culture and Nature in World Heritage: -- Rethinking the Contribution of Connecting Culture and Nature to the World Heritage Convention, Prof HAN Feng, CAUP Tongji University, China; Vice President of ICOMOS-IFLA International Scientific Committee of Cultural Landscapes (ISCCLs), explained some of the key concepts of Western philosophy, the World Heritage values as defined in the Convention and the World Heritage Criteria, and the categories defined by World Heritage and finally discussed the challenges of connecting Culture and Nature. She highlighted the different concepts between West and East, referring notably to Classic Philosophy based on a patriarchal dualist tradition based on separating humans and nature and considering the superiority of humans over nature and women. She presented some key philosophical environmental ethics questions: 1. Instrumental value or intrinsic value? 2. What is the origin of heritage value? 3. Located subjectively or objectively? 4. Who makes ethical decisions when values come into conflict? 5. Ethical monism or pluralism?

She detailed where natural and cultural heritage values stood within the10 World Heritage criteria used to define Outstanding Universal Values and how their understanding evolved taking the example of criteria vii on beauty and how in 2004 the distinct cultural and natural criteria list were merged into one list of criteria. She presented the evolution of the approach and understanding of the links between cultural and natural heritage within the World Heritage process, from the separate definition of natural and cultural heritage and the overlap in Articles 1 and 2 of the Convention text to the development of the cultural landscape idea of the “combined works of nature and man” which was reflected in the revised wording of the criteria and included in the Operational Guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. She further explained Cultural Landscapes not only link culture and nature but also intangible and tangible features, as well as evolving, living places with a context-based approach leading to a larger global diversity. She highlighted the difficulty to translate the concept in different regions of the world, in particular those where the divide is less strong or non-existent. In China, there are strictly speaking very few cultural landscapes although they could easily be acknowledged as Cultural Landscapes. She further noted that a regrettable outcome was that cultural landscapes fall under cultural heritage. She continued by exploring the challenges of linking culture and nature and how this approach allows bringing forward stronger linkage between landscapes, biodiversity, traditional knowledge, culture and sustainability, customary law and people in relation to sustainability. Finally, she ended by sharing examples of the identification of heritage values in Wulingyuan World Heritage natural site in China and highlighted how it is the profound interaction between man and nature that also leads to the need to consider whether many criteria can be shared.

04 Pecha Kucha

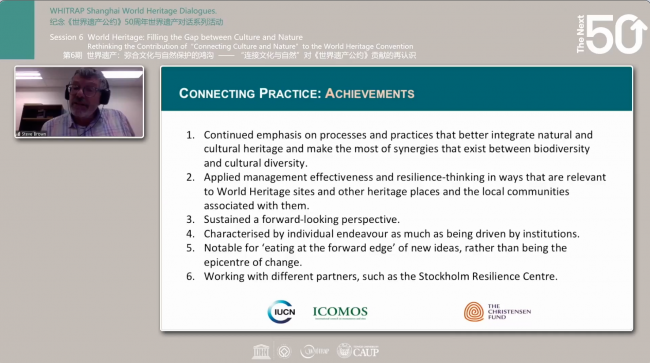

Image: Steve BROWN

Steve BROWN introduce the joint ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) and IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) “Connecting practice” project, launched in October 2013, which aims to define new methods and strategies to better integrate natural and cultural heritage within the World Heritage system and conservation practice in general. He presented the four phases of the project:

This project was a success, with many outstanding achievements.

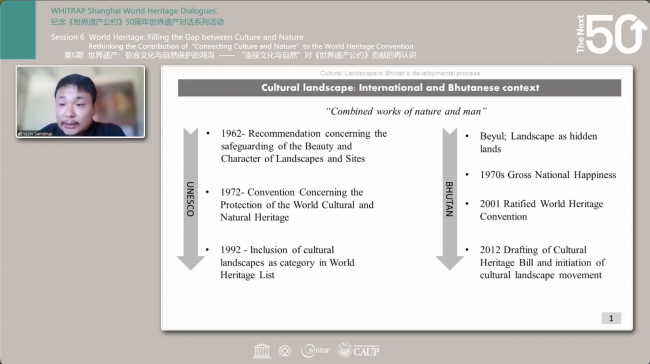

Image: Yeshi SAMDRUP

Yeshi SAMDRUP shared the evolution of the concepts of Cultural Landscape in the international context and in Bhutan’s developmental process from the 60s/70s to today. He recalled Bhutan is recognized as a whole for its unique landscape, which evolved through the interaction of people with nature and consists of cultural and natural elements that can reveal the aspects of the country’s culture, development and distinctiveness. He then further explained the development of the cultural landscape approach in Bhutan for conservation and development, based on sustainable and equitable socio-economic development, environmental conservation, preservation and promotion of culture, and good governance based on the Gross National Happiness indicator. He highlighted how the cultural landscape approach was a point of reference and guide to settlement planning in Bhutan and not only a heritage category. It is a tool to assess development activities through the establishment of specific policies and legal instruments including impact assessments and heritage surveys. Furthermore, he highlighted how the cultural landscape approach aims to foster traditional skills and knowledge to develop sustainable infrastructure as well as a concept of embracing cultural sites and heritage buildings. Finally, he explained Bhutan’s tourism policy focusing on respecting the unique characteristics of the landscape, its authenticity and integrity as well as promoting the country itself. In conclusion, he stated the key principle in Bhutan: “High Vale Low Volume”.

Image: ONO Wataru

ONO Wataru focused on the adequacy or non-adequacy of the current World Heritage system in encompassing cultural and natural values on discussed the need to rethink the criteria for justifying Outstanding Universal Values to better reflect the intrinsic link between culture and nature. He recalled the exceptional principles of the World Heritage Convention recognizing both cultural and natural heritage in one text. He further recalled that in the discussions on nature-culture in the World Heritage field, the binary or bipolar way of understanding nature vs. culture was relatively a Western way of thinking whereas they were not separated, in most non-Western ways of thinking, where culture was part of nature, in particular in Asia. However, despite different pre-existing concepts, the “culture separated from nature” approach was also used in the World Heritage system in Asia. He referred to the case of Mount Fuji, in Japan, which has natural values but was inscribed on the World Heritage List as a cultural property because it only met the criteria for cultural properties according to the World Heritage system. He pointed out also tentative sites, which did not meet natural criteria or cultural criteria alone but still had the potential of having Outstanding Universal Value. He provided another example, the Ama no Hashidate landscape in Japan, which is a unique combination of a natural sand bar and a pine tree grove that needs human intervention. Its value is difficult to justify under the existing criteria of Outstanding Universal Value or the existing category of Cultural Landscapes. ONO Wataru hoped the ongoing nature-culture discussion which has been ongoing for some years now will lead in the future to the creation of different criteria.

Lastly, ONO Wataru focused on the official “World Heritage Emblem”, which symbolizes the interdependence between cultural and natural heritage: a central square represents forms created by humans and the circle represents nature, the two being intimately linked. He shared his hypothesis that it was inspired by the ancient Chinese cosmology, Tianyuan Difang, which influenced Japan, particularly inspiring the construction of ancient Japanese palaces and capital cities.

Image: Maya ISHIZAWA

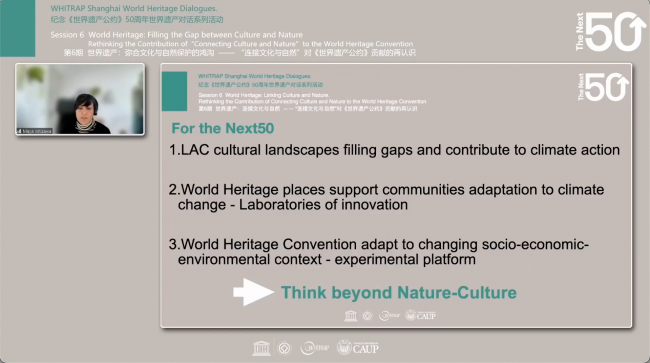

Maya ISHIZAWA presented some reflections from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) on the concept and definitions of cultural landscapes and their application in the region.

She started by discussing the cultural categories and historical periods developed in Modern history and heritage studies and the existing gaps. She explained the predominant types relate to pre-Hispanic, Colonial, Republican and modern periods. Whereas she further explained, other key cultural concepts were necessary to understand Andean heritage in the LAC region, such as a different perception of time and history, which is non-linear but expands and goes back and forth as heritage is living and present. She also stressed there was no distinction between what is human and non-human within the nature/culture categorization.

Regarding cultural landscapes, she pointed out there was a great variety of Cultural Landscapes in LAC, however hardly any of them were inscribed as such on the World Heritage List because their Outstanding Universal Value was not centred on the rich interactions between nature and culture but on other features, either natural or cultural, biodiversity or historical layers of significance. She suggested this under-representation on the List could be explained by the Cultural Landscape concept itself, where the divide between nature and culture still persists, as defining a cultural landscape requires distinguishing culture from its natural environment to identify the uniqueness of the interaction between the two. She further pointed out that the lack of adequate legal provisions and management models in the region as well as current heritage protection systems were built on the divide between nature and culture, further enforcing as a consequence, the Modern history perception of time, and colonial concepts of heritage.

She then detailed the case of Machu Picchu in Peru, inscribed in 1983 as a Mixed cultural and natural heritage property when the notion of Cultural Landscapes did not exist yet in the World Heritage Operational Guidelines. She continued by explaining this misunderstanding negatively impacted the designation of potential cultural landscapes and conservation and management.

Lastly, Maya ISHIZAWA stressed the importance of thinking beyond Nature-Culture and highlighted the following points in her conclusion:

To close, she underlined how the conceptual separation of nature and culture influenced heritage practice and policy-making, impacted the conservation of World Heritage sites, and the designation process itself in the LAC region. To move forward, she pointed out the need to explore more in-depth how LAC cultural landscapes could fill gaps and make the World Heritage List more representative, particularly rural and agricultural landscapes. They could be examples of sustainable relationships between human and non-human communities, which could in turn also help address the climate crisis as laboratories for innovation. The way forward, she suggested, was really to think beyond nature and culture.

Image: LIU Jian

LIU Jian’s presentation focused on the Beliefs Engraved on the Stones on the Tibetan Plateau: Cultural Landscape of Group of Mani Stones in Shiqu County.

Mani Stones, he explained are stacked and engraved stone slab shrines in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau where Tibetans make offerings and engage in religious practice such as practicing prayer wheels, rituals, and prayers. The tradition of stacking and engraving stone slabs with no mortar or a frame has been handed down from the prehistoric period. The group of Mani Stones in Shiqu country area nature-based cultural tradition influenced by the region's natural and social features:

The Tibetan Buddhist philosophy, which was supported by all tribes, played a key role in tribal social cohesion.

It was inappropriate for the nomadic people to place various large Buddha statues and numerous Buddhist scriptures representing “Dharma” in their tents.

There was no condition for building a temple complex because of the shortage of timber in the alpine area.

It was difficult to support the construction of a large religious cultural landscape because of the sparsity of residents. He continued by showcasing the Gsumge Mani Stone Castle as an example of a living heritage, because of the Tibetan natural worship and harmonious relationship between mountains and rivers, the social organization and beliefs, and distribution of tasks, the construction techniques and the religious utilization and social expression of regional folk belief.

He further explained the Mani stones reflected the widespread tradition of Tibetan people’s beliefs in the form of inscribed stones under the harsh geographical climate and nomadic lifestyle on the plateau. This unique type of cultural landscape has the potential to be a World Heritage Site with Outstanding Universal Value and could complement the World Heritage List in terms of the Mani stones in the alpine nomadic region having great significance for passing on local social value.

In conclusion, he highlighted that the power of tradition is still effective today to connect nature and culture. He pointed out, however, the impact of socio-economic development, on heritage sites which face various threats from modernization and the need to learn from the practice of "integration of culture and nature", to fully respect and promote tradition, and protect the cultural heritage and its surrounding natural environment in a holistic way.

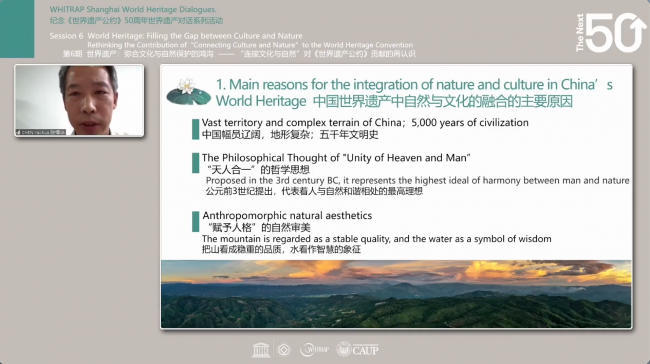

Image: CHEN Yaohua

CHEN Yaohua started by focusing on the Integration of Nature and Culture into China's World Heritage. He started by presenting the three main reasons for the integration of nature and culture into China’s World Heritage. Firstly, in space and time, China has a vast territory and complex terrain, with a civilization over 5000 years old. Secondly, Chinese philosophical concepts emphasize the integration and inherent relationship between, earth, “heaven and man united as one”. Developed in the 3rd century BC, this concept represents the highest ideal of harmony between nature and man. Thirdly, Chinese culture has an anthropomorphic approach to nature and nature’s aesthetics. A mountain for example is a symbol of stability and water of wisdom.

He continued by providing examples of culture inspired and influenced by nature. He explained how Mount Wuyi influenced Philosophy. The natural landscape of the site was the spiritual source of Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism thought. He also focused on another example, Mount Huang, which, with its unique silhouette, strange pine trees, a sea of clouds, and hot springs influenced art and gave birth to the Huangshan school of painting. Mount Huangshan also influenced literature, the natural beauty giving birth to a renowned culture. The natural site has rich cultural relics.

He then pointed to the influence of culture on nature in particular regarding protection through legal instruments, such as, in the Song Dynasty, Emperor Zhenzong’s, 1008 edict proclaiming, "no woodcutting is allowed within seven miles of Mount Tai", or local officials ordering via 1292, “Zhiyuan Ban” to not pollute the Wangmu (Queen Mother Pool) in Tai’an in the Yuan Dynasty. He also referred to West Lake, which beauty was praised in poetry and protected as a National Key Scenic and Historic Area in 1982 and listed on the World Heritage list in 2011. It is one of China’s top 40 tourist attractions, receiving 28.14 million visitors in 2018.

Presenting the case of Mount Tai, a World Heritage Mixed property inscribed in 1987, CHEN Yaohua explained how the integration of culture and nature enhances the overall value of heritage. Mount Tai is one of the most sacred mountains in China. Its values, CHEN Yaohua recalled, are embedded in its natural features enhanced by human intervention and a symbolic belief system, linking the underworld, the human world and heaven.

In conclusion, CHEN Yaohua reiterated that China's understanding of the relationship between nature and culture had always been that of a strongly integrated interlinkage between mankind and nature.

05 Round Table

The round table was moderated by Prof HAN Feng, who summed up some of the key points addressed in the participant’s presentations and added some comments on the concepts and definitions of cultural landscapes, regional specificities, the definition and understanding of the cultural and natural features and their interrelation with the World Heritage nomination process and management.

She mentioned the importance of identifying the intrinsic values or the instrumental values of natural features because these values can benefit human beings in particular in terms of achieving sustainable development. She then invited in turn discussants to reflect on two questions:

Does bridging the divides and differences between nature and culture and addressing the nature-culture linkage improve the understanding of what has value? Does it influence the conservation and management of heritage? Opportunities and challenges.

Does bridging the divides and differences between nature and culture and addressing the nature-culture linkage allow us to mitigate key environmental challenges in and beyond World Heritage such as impacts of climate change, improving quality of life, and social and environmental sustainability?

Throughout the Round Table, the moderator Prof. HAN Feng and the participants stressed the importance of the culture-nature linkage and how it was a key concept in Asia and the Pacific region, historically and today. In relation to identifying heritage values, they highlighted that although the World Heritage Convention integrated Cultural Natural heritage in one single text, including Mixed sites, the World Heritage List, until fairly recently, did not reflect properly the intrinsic complexity of the nature-culture ties, because of the World Heritage process itself – including the Operational Guidelines and the criteria for justifying Outstanding Universal Value -- as well as institutional and legal frameworks in most countries. They discussed at length the Cultural Landscape concept, developed and included in the world heritage system in the 90s, to further valorise the interaction between Humankind and its environment, and how the use of the word culture in the Cultural Landscape concept was confusing in the Asia and Pacific region because nature was culture and culture was nature, “1 + 1 = 1”. They further discussed the lack of representative Cultural Landscapes on the World Heritage List in the Asia and Pacific region as well as in the Latin America and Caribbean region and pointed out that many sites listed in the earlier days of the convention could be re-evaluated as Cultural landscapes. They suggested the small number of Cultural Landscapes on the List was related to the difficulty of justifying the values of the sites with the existing World Heritage criteria, which don’t always allow for reflecting the complex nature and cultural features. They advocated further thinking on the criteria and revising them in the future. The round table allowed us to point out the growing importance given in the World Heritage system to people and how advocating the need to enhance traditional knowledge systems was a key priority in particular in rural areas, as well as considering the intrinsic values of heritage value as a solution to address key development issues such as mitigating climate change impacts. The examples provided, also showcased the impact of the culture-nature divide not only on the identification of values and their conservation but also on protection and management mechanisms because of an administrative divide and silo effect. Regarding landscapes, Lastly, participants also insisted on research and knowledge sharing to identify heritage values innovatively and develop knowledge useful to valorise traditional knowledge skills and heritage as a solution to review our approach to development.

They highlighted how considering nature and culture as one, allowed us to redefine heritage values focused on defining OUV, its protection and its management.

06 Wrap Up

Image: Marie-Noël TOURNOUX

Marie-Noël TOURNOUX, Project Director, WHITRAP Shanghai, wrapped up the round table. She started by pointing out how the World Heritage Convention was dynamic and its system evolved to reflect the change in approaches, such as acknowledging the role of people and local communities. She equally highlighted the recent trend to rethink the nature-culture link. This had and could further lead to reconsidering the values of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and those to come in particular Cultural Landscapes.

Among the man takeaways, she pointed out that participants:

Prof. HAN Feng added three points. Firstly, she stressed the importance of celebrating the 50th anniversary of the World Heritage Convention. The second was to thank the World Heritage Convention for bringing us together. And the third was an invitation to move forward, hand in hand on the connecting culture and nature journey. She thanked all the experts for their great contributions.

07 Conclusion

As the 6th dialogue was the last WHITRAP Shanghai World Heritage Dialogue of the series, Marie-Noël TOURNOUX thanked all the participants of the 6th Dialogue and all the participants from previous dialogues and co-organizers and moderators from CAUP and WHITRAP. She thanked Prof LI Xiangning Dean of CAUP Tongji University and Prof ZHOU Jian who made the WHITRAP Shanghai World Heritage Dialogues possible. She followed by recalling that an overall summary would be presented on the occasion of the international conference on "World Heritage and Urban-Rural Sustainable Development: Resilience and Innovation" also organized by WHITRAP and CAUP Tongji University on 15th and 16th November 2022.

She stressed how this series of Dialogues was an opportunity to develop further research and training activities in the Asia Pacific Region.

Typeset: JI Zhenjiang (Intern) |

- News | WHITRAP Shanghai and CNR-ISPC bilateral meeting

- News | WHITRAP meets Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine

- WHITRAP Hosting "Workshop on Preliminary Assessment for National Focal Points of the Asia Region" in Chengdu

- WHITRAP Shanghai meets UNESCO

- INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE PRELIMINARY ANNOUNCEMENT & CALL FOR PAPERS

- Observation of the 46th Session of the World Heritage Committee

Copyright © 2009-2012 World Heritage Institute of Training and Research-Asia and Pacific (shanghai)